Kashmir II

We were foolish enough to explore the famous 'Shalimar Bag' (Bag, pronounced Bahg means garden) on a public holiday where the terraces were full of sightseers. Suffice it to say that the Persian word for garden is 'Paradise' and one of the great Mogul Emperors visiting Shalimar made the remark that has become so famous. "If Heaven is on Earth, it is here, it is here." I like to think that he said it standing at the bottom of the great staircase that rises from the very bottom of the garden and goes to the very top. It is not, of course, a staircase but a great waterfall but alas, when we saw it there was no running water there.We sat on the grass and ate the lunch that we brought. Suddenly there was a shout from a terrace just above us. "Shehprabha!" She looked up as it sounded like a shout from a friend and the delighted fans, a small group of young people had found her out. They laughed and cheered. Although she wanted to be incognito there was no doubt that she was delighted to be recognised. I soon became used to the incongruity of wanting privacy coupled with the pleasure of recognition. Even Film Stars are human.

Sneh did not drink but I had managed to wheedle out of the bar steward at Risalpur a bottle of Liebfraumilch believing that if she was to drink at all this would be wine for her. The very possession of such a bottle was something of a triumph in 1944. It was candlelit dinner for two, if there was a special reason for it I have sadly forgotten. I poured two glasses, waited until I judged it right to do so and raising my glass said "Cheers!" She looked at the floor and then at me, saying nothing; then a tear ran down her cheek. Unfairly perhaps; I was furious to think of wasting the bottle after so much effort. I picked it up and walked out on to the little entrance veranda above the steps and called for the shikara. A couple of strokes and he was there. I got in and asked him to row up the line which he did until there was a sound of male carousing from one of the houseboats. I was invited aboard and found myself facing a group of Army officers who were bent on enjoying their leave. I explained my plight and said that as I could not bear to waste the bottle would they accept it from me? I was offered a drink with them but declined, telling them of my dilemma.

I asked the shikara to take me back and as we were passing a hand appeared through the curtains, emptied the bottle into the water and then dropped the bottle. Sneh was a sad little thing that evening and I too found it difficult to smile. She had a brother whom I never met who had Tuberculosis. Western medicine was to her the 'Alternative Medicine' and she wanted to get him some pure musk from the scent gland of the Himalayan musk deer. She also wanted to get some Hawasil oil. Both of these products were, it seemed, obtainable from the right sources in Srinagar and our servant finally presented the trader who could help her.

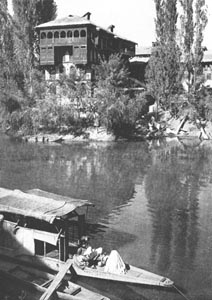

A Kashmir Waterway

He turned up at the houseboat and I left Sneh to sort things out. She usually wanted me around but I explained that these medical matters were beyond my ken. They haggled for quite a time over cups of tea and parted, he with heaven knows how many rupees and she with a small phial of some tarry substance and a bottle of a light oil. Well it looked like oil. She was so earnest about it all that I teased her a little and we left it at that.

On one of our trips into the city we were just standing on a bridge looking into the water when we found that two young army privates were doing just that by our side. I said something to one of them and soon we were in conversation. It was plain that Sneh sympathised with their lonely holiday because when we were about to leave she whispered to me "Do you think that they would like to come to dinner?" and I replied that I was sure that they would. They were quite overcome with gratitude. We took them down to the riverside and told our shikara to meet them at the appointed time and bring them to the houseboat.

We laid on some beer for them, Sneh was very sweet to them and busied herself preparing the food. We welcomed them aboard at the appointed time. They seemed so untouched by life. They were eighteen or nineteen and incredibly sweet, if I may use the word. They were only a few years younger than I but there was a great difference in experience. After all, there was the small matter of Sneh to explain but they took it all in their stride, becoming completely enthralled and why should I be surprised. The beer was expertly cooled in the lake by our shikara wallah who must have done the same for many Europeans. There was no need to mistrust him, after all he was a Muslim!

The lads were completely delighted and were surprisingly good company and after the meal were completely relaxed. To my shame I brought up the subject of the Hawasil oil and the musk. Sneh called my bluff and brought them out, telling them not to sniff too hard at the musk and that the oil came from the tail of a rare lizard. Also that it would help to cure her mother's arthritis. I voiced my doubts. Sneh then poured a little into the palm of my hand and told me to wait. After much discussion and general teasing she told me to turn my hand over, which I did. On the back, there were two patches, they could have been sweat but they were not. Feeling them, they were oily. The two lads looked at each other then at me. It defied all logic. I cannot not explain it now any more than I could then. For some reason an awkward silence followed. We were all quite nonplussed. The evening would not restart and soon afterwards I asked our Shikara wallah to take them back to the city.

|

|

|

|

The Jhelum Valley road |

|

We had already decided to take the road south towards Jammu as we left and started the long climb out of the enchanted vale, roughly following the path of the Jhelum river and then to pick up the valley of a tributary of the Chenab river. The road twisted and turned and suddenly we found ourselves in smoke from a forest fire and then in the fire itself. We looked back at the road and saw that it was engulfed in flames: there was nothing for it but to push on as fast as we could. The noise was deafening, from the crack of exploding pine trees and the flames but above all from the screaming of the fledgling birds trapped in their nests with the mature birds wheeling erratically above. The nightmare was over as suddenly as it had begun, the sun was shining and we were alive but choking with the oddly pleasant smell of woodsmoke.

We pulled in to the side of the road as soon as we could and were surprised that we had gone so far before stopping. Sneh was crying softly at the screaming, or was it one mind splitting shriek of the birds. I have heard it many times since but only in the memory of that terrible sound. We drove on with the river, thousands of feet below occasionally flashing like a quicksilver snake as the sun caught it. A few soldiers stopped us and directed us to a Dakh bungalow. It seemed that the Maharajah of Kashmir and Jummu was to pass this way so all mere mortals were to vacate the road. These Dakh bungalows were dotted along the long routes rather as the coaching inns had served travellers in Europe. Three British Army officers were already there, two captains and a Colonel who was considerably older. They were on their way to Srinagar and were more than a little interested in the forest fire. We wondered which direction the Maharajah was travelling and we all laughed at the bizarre thought of the fire extinguishing in his path rather like the Red Sea making a path for the Jews. It transpired that they were all doctors so after a couple of cups of tea I tentatively broached my problem with Hawasil oil. As I feared the two younger officers guffawed with laughter, asked me how long I had been in India and made some crack about the fakir climbing a rope and disappearing into the clouds.

Sneh caught my eye. She was obviously furious and about to leap to my defence but caught the warning and kept quiet. Noticing that their senior was not joining in the fun, they looked at him. He just said "I cannot comment and if you had been here as long as I have you would not be surprised at anything." He then questioned Sneh who's hurt dignity had turned to calm vindication and asked her about Vedic treatments. It all reminded me how closely I was questioned by doctors after being treated for undulant fever by Sneh's family. She remained fully in charge of the situation which turned to a lengthy conversation between her and the Colonel. The other two continually tried to engage me in private conversation. There were obviously many things that they wanted to ask me. They had ridiculed me, something that the mere male does not relish. I realised that to let their imaginations float would be better vindication that to elucidate so I left them guessing.

After the events of the day we were happy to arrive and we had to face the insecurities of parting, this time we were both aware that the next time we met I would be coming from 'beyond the Bramaputra.' (Anyone posted east of the river Bahmaputra automatically received an extra bonus as it was considered to be 'Operational'.) Meeting my brother officers confirmed that the squadron would be travelling east within a week or so. I asked her to write to my parents saying that her centre would be Calcutta for the foreseeable future. It would not have been difficult for me to get the information to England but it would not sound in the least suspicious coming from her.

This was a code I set up with them before I left U.K. I would quote the first line of a poem from my copy of the Oxford Book of English Verse which I always carried. My parents would then look up the number of the verse in an identical copy that I had given them and placing a protractor over Calcutta would read off the number in degrees. The next quotation would give the number of miles along the line. Thus, they would get a fairly accurate idea of my location.

Sneh seemed to have cried herself into a light trance at the prospect of our parting and I tried not to transmit my feeling of excitement at the prospect of 'ops' at last. In our last few moments of privacy I held her in my arms as so many times before but all energy seemed to have departed from her and the final poignant wave from the train was from someone I hardly knew.

Next: - Incident on the Khyber Pass

Previous: - Kashmir I

Edward Sparkes ©1998